News & Event

PRESS RELEASE: Red at First Sight but these Mites are Alright

Bright red pigment in red velvet mites protects them against harmful effects of UV radiation and heat

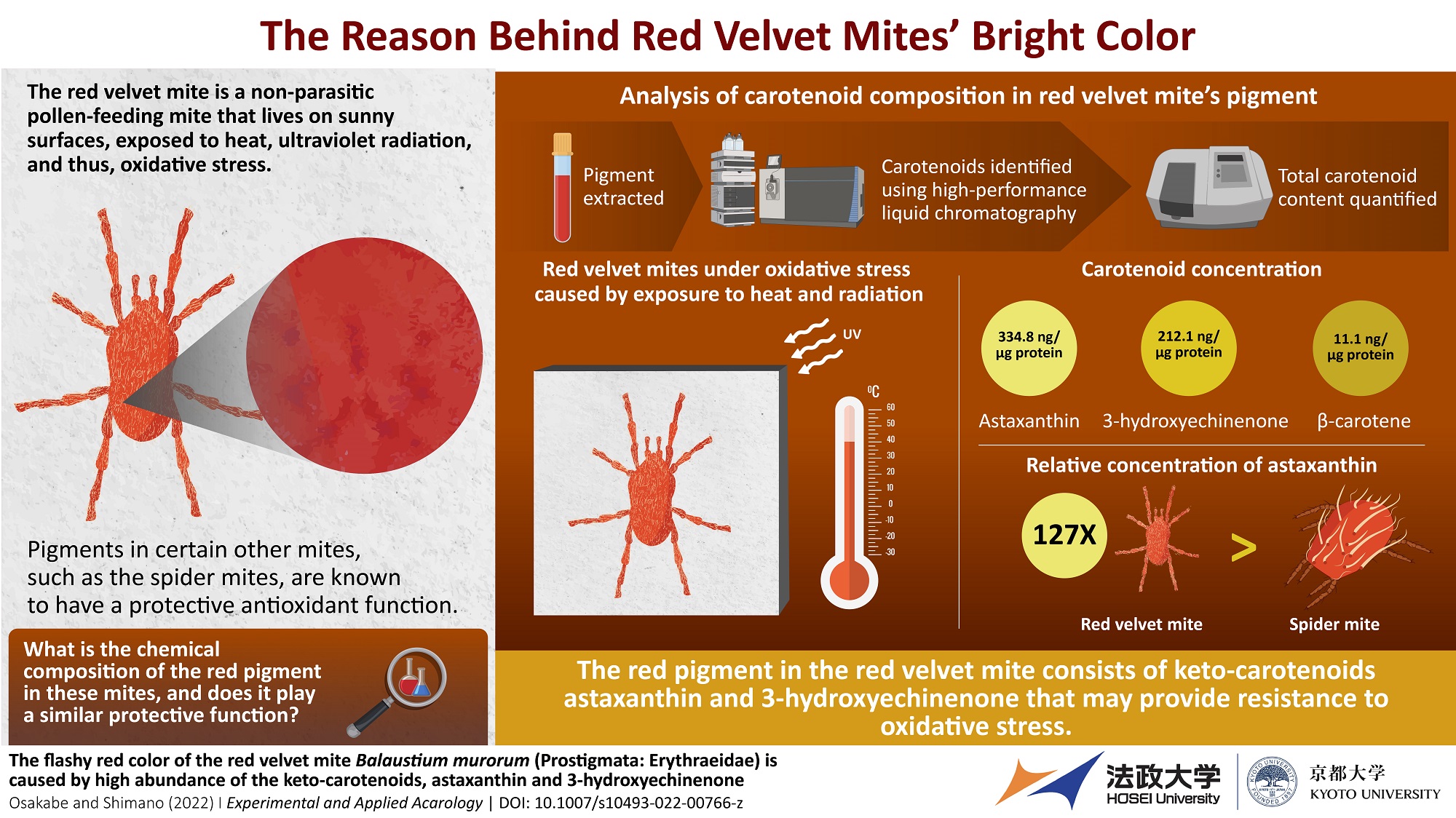

The red velvet mite, Balaustium murorum, is a free-living mite that lives on sunny surfaces like concrete. Despite being widely distributed throughout Eurasia in the northern hemisphere, the biological significance of their striking red color has not been scientifically investigated. Researchers from Japan have now unraveled this mystery. They found that the carotenoid pigment that gives these mites their distinct red color protects them against oxidative stress caused by exposure to heat and ultraviolet radiation.

The red velvet mite Balaustium murorum (Prostigmata: Erythraeidae)

Caption: Red velvet mites accumulate carotenoids from pollen that give them their bright red color

Credit: Satoshi Shimano from Hosei University and Masahiro Osakabe from Kyoto University

License: Original content

Living on the rugged landscape of rocks and concrete, the red velvet mite Balaustium murorum braves intense sunlight and ultraviolet radiation. These non-parasitic mites feed largely on pollen and emerge during spring from eggs that were laid during the previous summer. One can easily spot these critters crawling around due to their striking bright red color, making them an object of both fascination and fear, given the association of red with danger. The vivid coloration of these mites has not been subject to much scientific scrutiny. However, a study by researchers from Hosei University and Kyoto University, Japan, now suggests that the bright red pigment in these mites has a specific protective function.

"Every year, the number of online searches related to the red velvet mite shoots up in early spring. Many people consult the internet to know if this mite is harmful and whether its bright red color signifies that it has sucked blood. But the red velvet mite never acts as a parasite on other organisms,” says Professor Satoshi Shimano from Hosei University. "While we sigh in relief, knowing that these mites are mostly harmless, one does tend to wonder whether the distinct red color offers a specific survival advantage considering the harsh environments that red velvet mites live in."

Though none are as visually striking as the red velvet mites, several other mites, such as spider mites (Panonychus citri), display red pigmentation. Spider mites remain active during the day and are also exposed to intense sunlight. Being constantly exposed to solar radiation causes the production of harmful reactive oxygen species in the body leading to “oxidative stress”. To cope with oxidative stress, spider mites are known to accumulate the carotenoid astaxanthin, a powerful antioxidant, in their body. The accumulation of these carotenoids ultimately manifests as a deep red color on the spider mites’ bodies.

To investigate whether the red velvet mite's bright pigmentation plays a similar protective role, the researchers identified and quantified carotenoids present in the arachnid's body. A chemical-profiling analysis revealed that carotenoids in the red velvet mite were primarily composed of astaxanthin (60%), followed by 3-hydroxyechinenone (38%), both of which are known to be powerful antioxidants.

Professor Masahiro Osakabe from Kyoto University further adds, “Astaxanthin concentration in the red velvet mite was 127-fold higher than that in spider mite, Panonychus citri, which is an astaxanthin-rich species. This is one of the highest known levels of microarthropods, including crustaceans. Hence, the red velvet mite’s color is the result of high concentrations of keto-carotenoids, which act as antioxidants against reactive oxygen species that form in harsh environments, due to strong ultraviolet rays and radiant heat.”

While the flashy red color protects these mites from the harsh environment, one might wonder whether it is a double-edged sword, making them vulnerable and easily targeted by their natural predators. But Shimano and Osakabe say there is no need to worry since the mite is active only in early spring before other insects are fully active. In fact, this peculiar life cycle could be the reason why these mites prefer such hot environments. Furthermore, their natural enemies -- ants and predatory stink bugs -- do not have photoreceptors for red. So, their red color, which is unusually conspicuous to us humans on concrete, is not thought to affect the hunting behavior of their predators.

"Red velvet mites can stain white clothing due to their carotenoid-rich pigment if they get crushed underneath people. Fortunately, a quick and easy remedy is using ethanol commonly used in hand sanitizers," offers Shimano.

In conclusion, the red velvet mite’s peculiar color, a feature that many people find striking and potentially indicative of danger, has been revealed to be a benign protective feature. What appears to some people as an indication that the mite is harmful, is likely an adaptation that simply helps them remain active under intense sunlight.

The red velvet mite Balaustium murorum (Prostigmata: Erythraeidae)

Caption: Red velvet mites accumulate carotenoids from pollen that give them their bright red color

Credit: Takamasa Memoto

License: Original content

Reference

Authors: Masahiro Osakabe1, Satoshi Shimano2

Title of original paper: The flashy red color of the red velvet mite Balaustium murorum (Prostigmata: Erythraeidae) is caused by high abundance of the keto-carotenoids, astaxanthin and 3-hydroxyechinenone

Journal: Experimental and Applied Acarology

DOI: 10.1007/s10493-022-00766-z

Affiliations:

1Laboratory of Ecological Information, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, 606-8502 Kyoto, Japan

2Science Research Center, Hosei University, 2-17-1 Fujimi, Chiyoda-ku, 102-8160 Tokyo, Japan

About Professor Satoshi Shimano from Hosei University

Satoshi Shimano is a professor at Hosei University, Japan. He has published over 150 scientific articles in a wide range of fields including Systematics, Taxonomy, Soil Zoology, Acarology, and Protistology.

About Professor Masahiro Osakabe from Kyoto University

Masahiro Osakabe recently retired from the Graduate School of Agriculture at Kyoto University as an Associate Professor. He has over 40 years of research experience and has published over 110 scientific papers in research fields including Acarology, Entomology and Pest Management.

About Hosei University

Hosei University is one of the leading private universities in Tokyo, Japan. The University offers international courses in many disciplines and has a long and rich history. Hosei University was founded as a school of Law in 1880 and evolved into a private university by 1920.

It is also home to multiple research centers, which conduct advanced research on various fields, including nanotechnology, sustainability, ecology, and more.

The University has three main campuses—Ichigaya, Koganei, and Tama, located across Tokyo.

For more information please see: https://www.hosei.ac.jp/english/

About Kyoto University

Kyoto University is one of Japan and Asia's premier research institutions, founded in 1897 and responsible for producing numerous Nobel laureates and winners of other prestigious international prizes. A broad curriculum across the arts and sciences at both undergraduate and graduate levels is complemented by numerous research centers, as well as facilities and offices around Japan and the world. For more information please see: http://www.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en

Media Contact

Office of the President Public Relations Section, Hosei University

pr@adm.hosei.ac.jp